Born in 1904 in small-town Virginia, Undine Smith Moore made her mark as a talented composer, pianist, and exceptional teacher. She earned her title, “the Dean of Black Women Composers,” by continuously giving her all to her students at Virginia State College and through her songs, piano pieces, and spirituals, which many are rediscovering today.

Moore’s family focused heavily on music, so it was no surprise that she quickly took up the piano. At church and home, the entire family celebrated with singing and playing. After moving to Petersburg, VA, in 1908 with her family, Undine started taking lessons with Lillian Allen Darden. She trained diligently, learning the ins and outs of becoming a top-notch classical pianist.

Following her love of music, Moore attended the historically black college, Fisk University, for her undergraduate in piano studies. In 1924, Julliard, a world-renowned conservatory, recognized Moore’s talent by offering her a full scholarship. However, she chose to accept an offer to become the supervisor of music in Goldsboro, North Carolina. The following year, she joined the music faculty of Virginia State College while also commuting to Columbia University for her Master’s.

During her long tenure at Virginia State, Moore became the backbone of the department. Through her efforts in co-founding and directing the Black Music Center at Virginia State, thousands of young Black musicians could experience the music of top Black composers and performers. They could learn from leading Black lecturers in a variety of musical fields, including blues and jazz. At the time, few college curriculums included music by Black composers, and Moore pushed to change that.

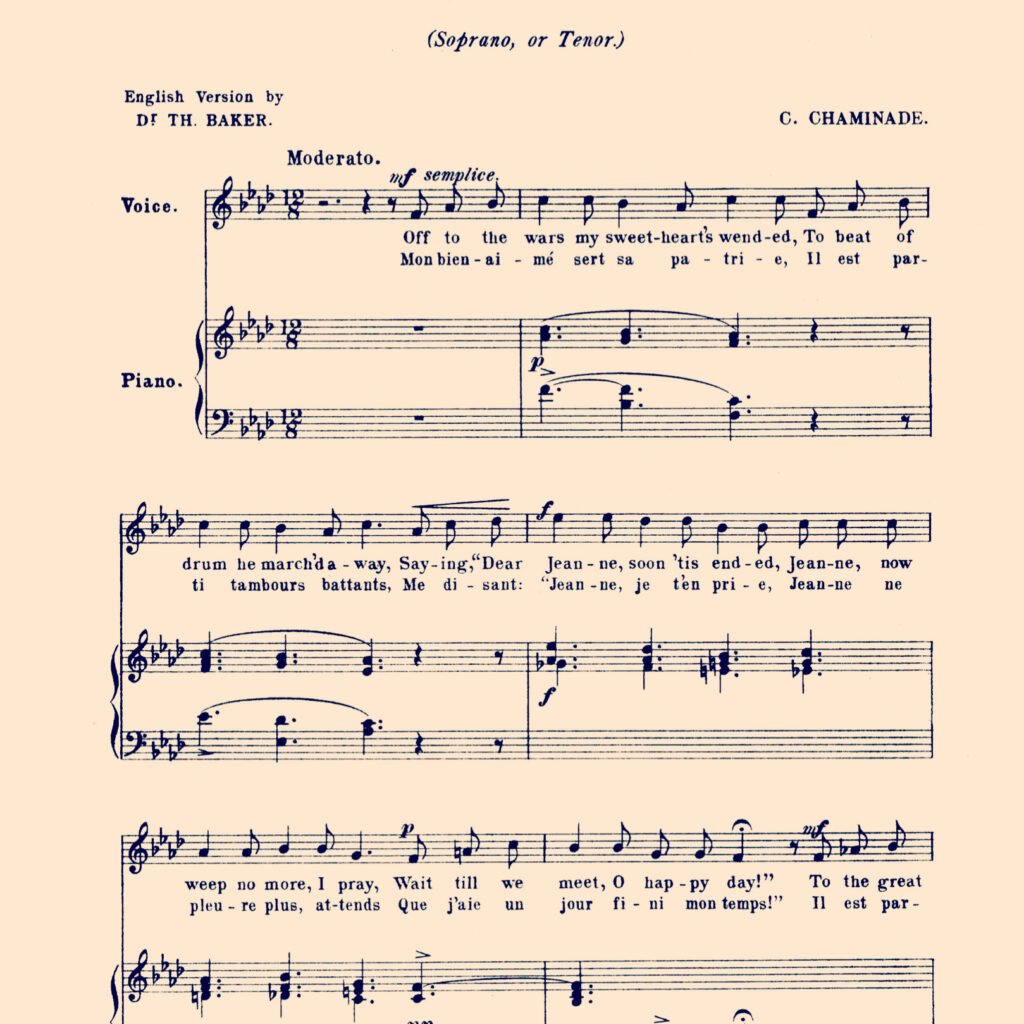

Although Moore didn’t consider herself a composer, she wrote and arranged over 100 pieces, primarily for voice and piano. When asked about composing, she said, “One of the most evil effects of racism in my time was the limits it placed upon the aspirations of blacks, so that though I have been ‘making up’ and creating music all my life, in my childhood or even in college I would not have thought of calling myself a composer or aspiring to be one.” It wasn’t until she retired from teaching that she truly began to think of herself as a composer rather than a teacher.

Moore also frequently spoke about the issues concerning women in classical music, particularly in composition and conducting. She believed that because both conductors and composers serve as authority figures in the musical world, it was no surprise that women found it difficult to break into these fields. Additionally, Moore often expressed that because women had to care for the “minutia of daily life,” like taking care of children and the house, they had less mental space to find the freedom needed for composition. This theme is a recurring one, with social norms forcing women to take more mental energy to run the household, care for children, and feed their families. From Clara Schumann to Amy Beach, women composers across history have found it challenging to balance the needs of the family and their need to compose.

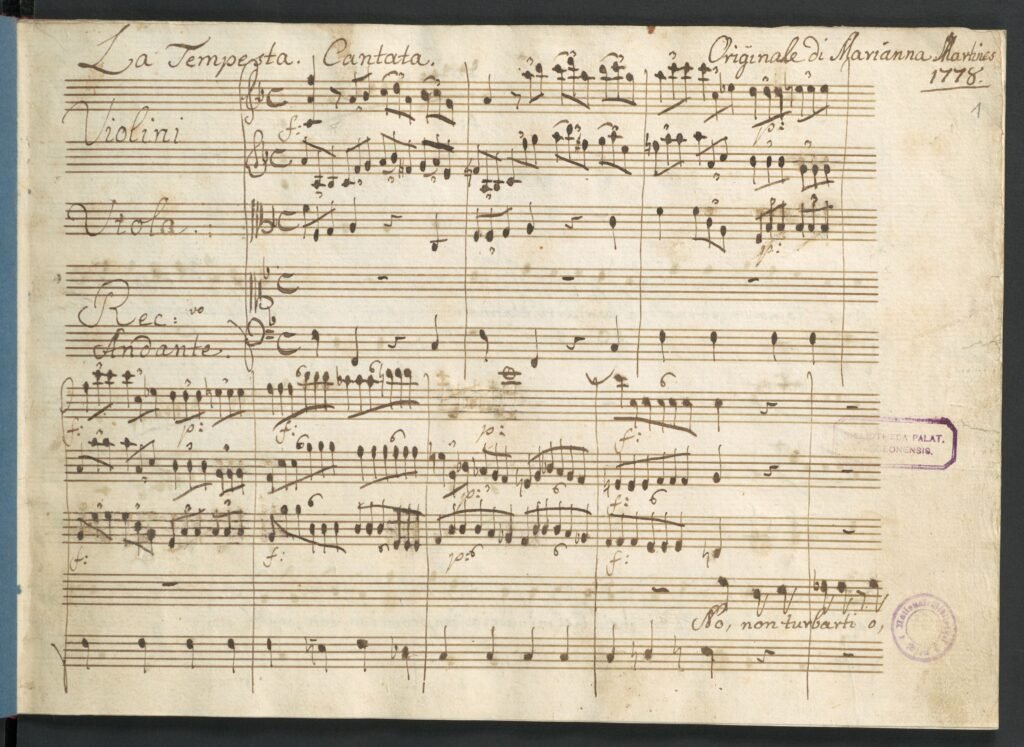

Through Moore’s work, thousands of young students learned about Black and female composers and performers that would otherwise have disappeared into history. She also gave us a wide range of fantastic pieces, including art songs, arrangements of spirituals, and a cantata featuring her own libretto, Scenes from the life of a Martyr, which honors Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Throughout her life, Moore received many awards and recognitions, including an honorary doctorate from Virginia State and Indiana University and the Humanitarian Award from Fisk University. In 1977, Virginia named her its music laureate, and in 1985 the state awarded her the Virginia Governor’s Award in the Arts. She passed away from a stroke on February 6, 1989.

While preparing for a competition, I came across Moore’s arrangement of Come Down Angels. It’s a beautiful arrangement, and I hope you enjoy our rendition of it.

To learn more about Undine Smith Moore, check out From Spirituals to Symphonies: African American Women Composers and their Music by Helen Walker-Hill. There’s also The Gershwin Initiative and Music by Black Composers.

You can find her music in some anthologies, including Hildegard Publishing Company’s Art Songs & Spirituals by African-American Women Composers.